The First Black City: The Founding

- educ82024

- Oct 6, 2025

- 5 min read

Lincoln Heights didn't happen by accident. It happened because Black folks refused to accept that freedom meant settling for the scraps white America was willing to throw our way. When we talk about "the first Black city," we're not just talking about dates on a map or incorporation papers filed in some courthouse. We're talking about audacity. We're talking about the radical act of saying: "We deserve better. And we're going to build it ourselves."

This is the story of how Lincoln Heights became more than a place: how it became a declaration of independence written in brick, mortar, and unshakeable determination.

The Dream Before the Foundation

Picture this: It's the 1940s. Black families across the Midwest are tired of being told where they can live, where they can work, where their children can go to school. Redlining isn't just a policy: it's a daily reminder that your American dream has asterisks, conditions, and a whole lot of "not here, not now, not ever."

But in the hills north of Cincinnati, something different was stirring. Black families weren't just dreaming of homeownership: they were dreaming of home rule. They weren't just imagining better neighborhoods: they were imagining neighborhoods where they set the rules, elected the officials, and determined the future.

This wasn't wishful thinking. This was strategic vision. The founders of Lincoln Heights understood something that still rings true today: Liberation isn't something you ask for. It's something you build.

The Architects of Audacity

The story of Lincoln Heights begins with people who refused to accept that separate had to mean unequal: and who decided that if America wouldn't give them equal, they'd create something better. These weren't just homebuyers. These were nation-builders.

Led by visionaries who understood that political power flows from economic power, and economic power flows from owning the ground you stand on, Lincoln Heights emerged as a radical experiment in Black self-determination. While other communities were fighting for integration, Lincoln Heights was fighting for something even more revolutionary: the right to govern themselves.

The founding families: names like the Baileys, the Washingtons, the Johnsons: they didn't just buy property. They bought possibility. They didn't just move to a new address. They moved toward a new model of what Black life in America could look like when we stopped asking for permission and started building power.

Breaking Ground, Breaking Barriers

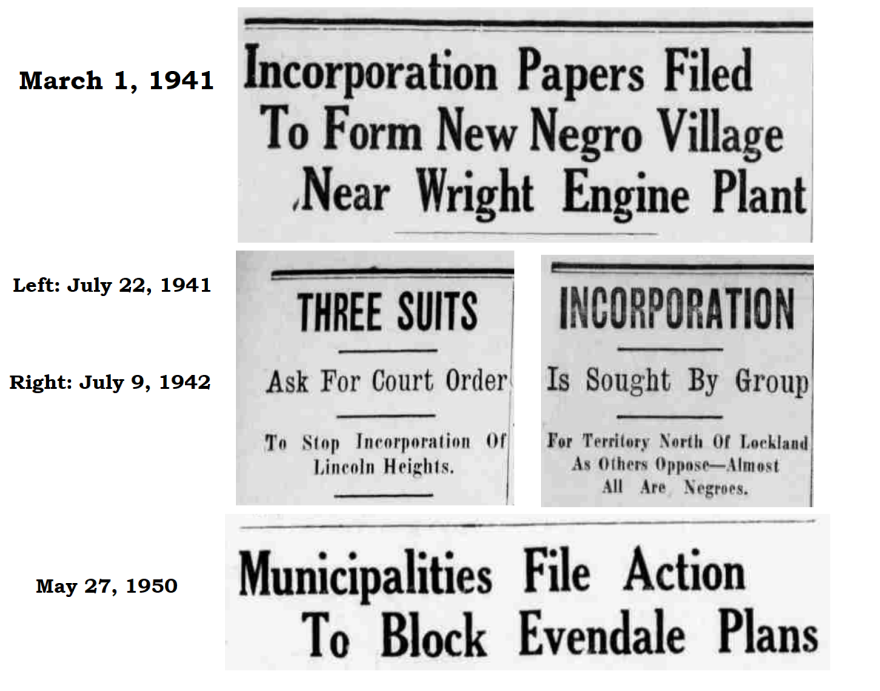

When Lincoln Heights incorporated as a village in 1946, it wasn't just another suburb sprouting up in post-war America. It was a direct challenge to every assumption about where Black folks belonged in this country. While the GI Bill was helping white veterans buy homes in segregated suburbs, Black veterans and their families were creating their own American dream: one that didn't require white approval or validation.

The incorporation wasn't just legal paperwork. It was a revolutionary act. Every signature on those documents was a vote of no confidence in the status quo. Every family that moved in was making a statement: We belong wherever we choose to build.

This wasn't about separatism. This was about self-determination. There's a difference. Separatism says "we can't be together." Self-determination says "we don't need your permission to be powerful."

Building More Than Houses

What made Lincoln Heights revolutionary wasn't just that Black families could buy homes there. What made it revolutionary was that Black families could shape the entire community's destiny. The mayor was Black. The city council was Black. The school board was Black. The police chief was Black. The fire chief was Black.

This wasn't tokenism. This wasn't representation. This was governance.

For the first time in American history, Black children in Lincoln Heights could grow up seeing themselves in every position of authority in their community. They didn't have to imagine what Black leadership looked like: they lived it every day. They didn't have to dream about Black excellence: they were surrounded by it.

The businesses were Black-owned. The churches were Black-led. The schools were Black-operated. This wasn't a ghetto: this was a kingdom. This wasn't segregation: this was sovereignty.

The Economics of Freedom

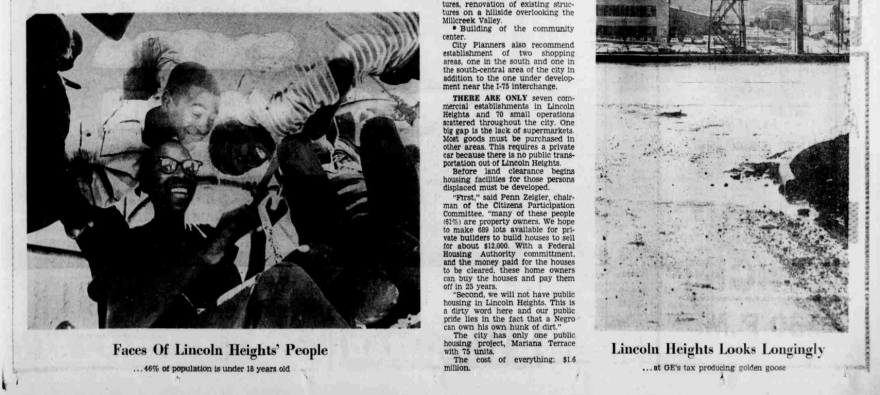

Lincoln Heights proved something that America didn't want to acknowledge: Black people didn't need integration to thrive. We needed investment, ownership, and control. The economic foundation of Lincoln Heights was revolutionary precisely because it was self-sustaining.

Black-owned businesses served Black families. Black professionals lived alongside Black laborers. Black teachers taught Black children who would grow up to become Black leaders in their own right. The money stayed in the community. The wealth stayed in the community. The power stayed in the community.

This economic model challenged every narrative about Black dependency and white necessity. Lincoln Heights didn't need white customers to succeed. It didn't need white investors to grow. It didn't need white politicians to govern. It needed what every thriving community needs: vision, investment, and the freedom to determine its own destiny.

The Ripple Effect of Revolution

The founding of Lincoln Heights sent shockwaves through Ohio and beyond. If Black folks could build their own city in the hills outside Cincinnati, what else could they build? If they could elect their own mayors and run their own schools, what other forms of self-governance were possible?

Lincoln Heights became a model that inspired Black communities across the Midwest. It proved that the dream of Black political power wasn't just a dream: it was an achievable reality for communities willing to organize, invest, and build.

But more than that, Lincoln Heights became a training ground for Black leadership that would influence civil rights organizing for generations. The skills learned in city council meetings, school board elections, and community organizing in Lincoln Heights would be carried into broader struggles for justice and equality.

Lessons from the Foundation

The founding of Lincoln Heights teaches us something that's as relevant today as it was in 1946: Power isn't given. It's taken. It's built. It's organized. It's sustained through community investment and collective vision.

The founders of Lincoln Heights didn't wait for permission to create the community they wanted. They didn't wait for white approval to pursue their dreams. They didn't wait for perfect conditions to start building.

They started where they were, with what they had, for the future they envisioned.

That's the blueprint. That's the model. That's the foundation that still stands today, waiting for a new generation to build upon it.

Reclaiming the Vision

Today, when we talk about Lincoln Heights, we're not just talking about history. We're talking about possibility. The same vision that created the first Black city in Ohio is the same vision that can recreate Black political and economic power anywhere we choose to organize and build.

The founders of Lincoln Heights understood something we need to remember: Liberation isn't a destination. It's a practice. It's not something we achieve once and maintain forever. It's something we build every day, in every decision, in every investment, in every vote.

Lincoln Heights was founded on the radical belief that Black communities could govern themselves, build wealth for themselves, and determine their own futures. That belief isn't history. It's prophecy. It's not what we once were. It's what we can be again.

The foundation is still there. The blueprint is still there. The audacity is still there.

The question isn't whether we can build Black political and economic power. Lincoln Heights proved we can.

The question is whether we will.

The foundation was laid in 1946. The building continues today. The future belongs to those willing to pick up the tools and keep building.

This is Lincoln Heights. This is our foundation. This is our future.

Let's build.

Comments